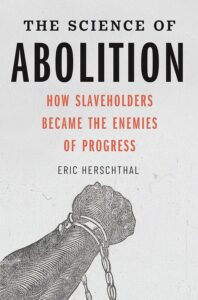

The Science of Abolition: How Slaveholders Became the Enemies of Progress. By Eric Herschthal. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021. pp. 326. Cloth, $32.50.)

The Science of Abolition: How Slaveholders Became the Enemies of Progress. By Eric Herschthal. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021. pp. 326. Cloth, $32.50.)

The Science of Abolition proports to be a book that offers a new view of the role science played in antislavery and abolitionist thought. Herschthal wants to move beyond the examination of race science to postulate how other sciences affected abolitionist rhetoric and how participants in the movement shaped that rhetoric to their own means. In the introduction to The Science of Abolition, Herschthal makes his distinction that his historical actors are not scientists, but men of science, saying

Becoming a man of science required little formal training and a fair amount of networking and self-fashioning; gaining entry to the right social networks; adopting the proper tone of deference and gentlemanly decorum, publishing in respectable journals; finding wealthy patrons. In addition, before the 1830s, being a man of science was rarely a full-time job and more a learned hobby. The most prominent men of science in this period…supported themselves with other activities…(4).

Herschthal makes the argument that abolitionists used sciences other than racial science to argue against slavery. Defining the science of abolition, he says:

Though proslavery racial science of this period is well known, few scholars have explored the vast array of scientific knowledge beyond racial science that also bore on the question of slavery – from ideas rooted in chemistry and geology to those based on medicine, demography, and engineering. More to the point, few have realized that antislavery advocates, as much as their proslavery adversaries, relied on scientific discourse to defend their views. Taken together, this antislavery scientific discourse amounts to what I call the science of abolition – a wide range of scientific arguments that helped legitimate the antislavery movement and that ultimately cast slaveholders as unscientific and premodern: the enemies of progress.” (2).

But the lines between proslavery and antislavery advocates are blurred. Herschthal spends several chapters outlining how many abolitionists soft-pedalled their rhetoric due to the fact that they either had close ties to slaveholders or because they didn’t want to support an abolitionist regime that might alienate potential followers, North and South, or both of these regions. For example, Benjamin Silliman, Yale’s first professor of chemistry, owed funding for his position in part to slaveholders. But the gradual cutting of ties with these abolitionist sponsors and a gradual view of emancipation seems to come a bit quickly at the end of the book.

It was interesting to trace the progression of abolitionist thought. Herschthal starts with abolitionist’s beliefs that colonization was the only solution to the problem of abolition. The science he uses here had elite white men of science promote Sierra Leone as a colony ripe for agricultural success, whereas the reality of the colony’s land turned out to be deficient in providing nourishment and self-sufficiency for colonists.

Planters’ failure to embrace modern farming techniques like the plow enabled abolitionists to paint them as backward and anti-technology. Abolitionists made the argument that if planters would employ labor saving devices, they would be able to drastically lessen their dependence on enslaved labor. But for slaveholders who did try technologies like the plow, they found it unsuited to farming conditions in the American South, or found slave labor too profitable to be incentivized to change. The same may be said of the flax processing machines invented in England prior to the Civil War in America. Cotton remained the supreme product.

Herschthal also can’t quite escape the inevitability of racial science being part of the narrative of the science of abolition. He writes at length about polygenesis and monogenesis, and how this relates to “hard” science is a bit unclear. Men of science attempted to use science to prove or disprove one or the other of the theories. Men of science either claimed that science proved one race was superior to the other, or, in the case of abolitionists, that if the races weren’t yet equal, the enslaved were human and could improve over time.

One thing Herschthal does discuss but only mentions by name once, is the theory of racial uplift. Blacks and abolitionists believed that by becoming men of science and proving their intellectual and cultural equality, Blacks could prove they were equals with white men. Becoming an abolitionist and using science to argue in favor of abolition might allow Black men to gain respect from their white peers, if not from the nation at large. Uplift is always a tricky path to walk, and has caused much controversy in the Black community, especially since it didn’t work. Black men of science like Benjamin Banneker believed that by joining the community of elite white men of science he was standing in as a respected avatar for his race, not as a race traitor. Herschthal says:

“After all [Paul] Cuffe, [a free African American sailor], routinely argued that Black people needed to embrace white culture in order for whites to accept them – and that included an embrace of science.” (176).

Further,

…Black abolitionists also had reasons [to support science] particular to their communities. For many Black leaders, supporting scientific solutions merged with a larger integrationist philosophy. Embracing science signaled a commitment to the nation’s economic development, and, by extension, to the nation itself. Black integrationists, women as well as men, urged Black audiences to engage with scientific knowledge whenever they could. (240).

The armchair nature of the pursuits of men of science meant that Blacks could enter this discourse given they had the freedom and education to do so. Of course, this is did not mean that abolitionists were not also racist and that they all welcomed Black men of science with open arms. But the movement allowed for their Black entry into a community of abolition, even at a diminished status. Some Black men of science would become poster boys of abolitionist science, demonstrating that Blacks could uplift themselves at least to a certain height, if not full equality. But Herschthal explains the limits of black participation in the ultimate success of abolition, writing

But modern-day interpretations that highlight Black agency do not necessarily reflect the views of historical subjects. To many white people, both during and after slavery, emancipation came about not because of the agency of Black people, but because of the backwardness of slaveholders themselves.” (247).

The Science of Abolition portrays an important facet of the battle against slavery. One thing that is abundantly clear is how quickly abolitionists ideas could slide into racism, especially when Northerners worked with Southerners to tackle the problem of abolition. Men of science helped win abolition by firmly and consistently turning against Southern slaveowners and projecting them as technologically backwards. Slaveowners refused to take advantage of new technologies and instead clung to the morally bankrupt state of slave owning.

But it should be remembered that for decades abolitionists believed that the only way to abolish slavery was to ship all the enslaved off to overseas colonies in Africa. Blacks, in this view, had no place in America. Black and white abolitionists could actually use this as a point of agreement with enslavers, some of whom claimed to be fine with the idea as long as someone compensated them for their lost slaves. But the idea was not popular enough with either Blacks or whites to ever actually take off. Contrary to claims from men of science, Sierra Leone was largely inhospitable, and Blacks who had been in the Americas for generations did not want to leave what they considered to be their true home and the rest of their families.

I think this book makes an important contribution to arguments about science and race. I am not a scholar of slavery or abolition, but from where I sit, this book supplements what I have read about these subjects. I would like to learn more about the role of science in slaveholding. It would be interesting to learn more about ideas of divergence and convergence between abolitionists and slaveholders on science and technology in the role of slaveholding or a slave-based economy. It would also be helpful to understand more about how the populace at large felt about these scientific approaches to slavery. Herschthal focuses on elite men.

This book begs to be inserted into a historiography of slavery. It would work well in a graduate level course that can situate in that academic field.

Out of the Depths: A History of Shipwrecks. By Alan G. Jamieson. (London, Reaktion Books Ltd, 2022. pp. 342. Cloth $42.00.)

Out of the Depths: A History of Shipwrecks. By Alan G. Jamieson. (London, Reaktion Books Ltd, 2022. pp. 342. Cloth $42.00.)