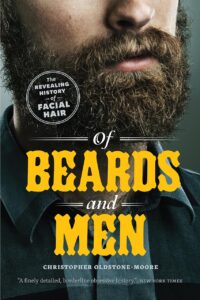

Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair – Christopher Oldstone-Moore

Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair. By Christopher Oldstone-Moore. (University of Chicago Press: Chicago. 338 pages. Cloth $32.00. Paper $19.00.)

Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair. By Christopher Oldstone-Moore. (University of Chicago Press: Chicago. 338 pages. Cloth $32.00. Paper $19.00.)

At the end of his introduction to Of Beards and Men, Oldstone-Moore sets boundaries for his study He writes: “Limitation of space and sources dictate that this initial exploration of beard history focus primarily on the elite men in Western Europe and North America who had time and resources to shape their bodies as they deemed appropriate, and whose choices dictated social norms.” (4)

Historians are allowed to lay out the boundaries of their topics, and it is legitimate to limit narratives where no sources can be found. But I have to take issue with the focus on elite men. Once into the 1960s and 1970s, at the very least, there had to be sources for all social strata on the politics of facial hair. It seems to me a gross oversight to leave out the politics of Black facial hair simply because they do not fit Oldstone-Moore’s definition of elites, which he views as white Europeans and those of European descent. He never explicitly defines what he means by the “West,” though North America does seem a bit more specific if not inclusive all those social and racial groups present in North America. For Oldstone-Moore, the politics of facial hair means white facial hair.

Surely there were elite Black men both within and without of their communities in the West, such as Martin Luther King, who wore facial hair. Why are he and other black “elites” like him excluded from this narrative? Why is there nothing about social movements like the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panthers? Black hair has always been implicitly and explicitly political, and I don’t understand why they are excluded. They have been a part of the western hemisphere since the 15th century, especially in North America. Their African roots do not preclude them from a place in a book about the politics of facial hair in the West.

I think Oldstone-Moore writes himself into a corner by only focusing on elites. He never offers a definition of what an “elite” is, and the argument that other social classes may not appear in the narrative seems limited to me. The omission of Black people and other minorities limits his work. Had he gone into more details about the nature of his sources, exclusion of minority groups in the West might make more sense. As is the vague definitions and boundaries leads to a work that seems to undermine his own purpose. We will have to wait for other authors to examine what Oldstone-Moore has left out.