Slaves Waiting for Sale – Maurie D. McInnis

Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade. By Maurie D. McInnis. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011. 227pp. Paper, $33.00. Cloth $99.00.)

Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade. By Maurie D. McInnis. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011. 227pp. Paper, $33.00. Cloth $99.00.)

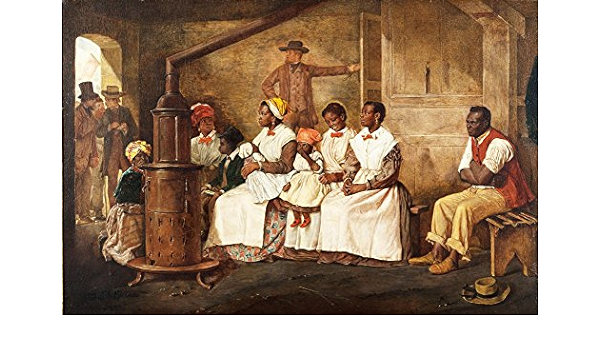

In Slaves Waiting for Sale, Maurie D. McInnis sets out to understand the slave trade through the use of visual sources created by white male artists as they depicted various scenes brought about by that trade. McInnis focuses especially on the eponymous 1861 painting, Slaves Waiting for Sale, painted by British artist Eyre Crowe. While on a visit to the United States with William Makepeace Thackeray, Crowe witnessed a slave auction in Richmond, Virginia, that inspired the painting. McInnis claims that his painting is unique because, as opposed to depicting the sale itself, a common feature of abolitionist imagery, he depicted slaves waiting to be a sold, a wide range of emotion playing across their faces. McInnis particularly focuses on the enslaved man in the image, who with arm’s cross appears in what McInnis thinks is a surprisingly defiant position. For McInnis this painting gives us new insight into the brutality of the slave trade, as well as exploring how different visual artists represented it.

Crowe painted this image from a sketch he took at a Richmond slave sale, an action that almost got him tossed out when slave buyers and traders noticed what he was doing. McInnis believes this painting is a singular work of art that expertly expresses the cruelty of the slave trade by highlighting how slaves faced their impending sale, clinging to their families and displaying rebellion, even if it is just expressed in a body language. As revealed in Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul, anything that the enslaved did that might reveal the tragedy at the heart of the slave trade could tank a sale and ruin the reputation of traders and buyers. McInnis also paints an interesting picture of the Richmond slave market, something that was new to me.

Crowe painted this image from a sketch he took at a Richmond slave sale, an action that almost got him tossed out when slave buyers and traders noticed what he was doing. McInnis believes this painting is a singular work of art that expertly expresses the cruelty of the slave trade by highlighting how slaves faced their impending sale, clinging to their families and displaying rebellion, even if it is just expressed in a body language. As revealed in Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul, anything that the enslaved did that might reveal the tragedy at the heart of the slave trade could tank a sale and ruin the reputation of traders and buyers. McInnis also paints an interesting picture of the Richmond slave market, something that was new to me.

What I think is missing here is a thorough examination of the origins of this image and those who made it possible. Crowe is a white male, and British, and so his painting is taken from that viewpoint. In a way he is representing what slave buyers and traders refused to acknowledge by painting a scene atypically depicted by other artists. He focus is on the human anticipation of the sale and not the rupture that was the auction itself. For McInnis, the waiting enslaved in Crowe’s painting reveal that the slave auction is only one rupture, that the enslaved have suffered rupture after rupture only to be faced with the utter devastation of the sale.

Similarly, all the white slave traders and enslavers are men; there is no mention of how white women might have played a role in the trade outside of fears of white slavery. This sexualizes white women and marginalizes them from a world they were very much a part of, as we know from They Were Her Property by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers. It could be that McInnis simply did not find images depicting female slave owners or participants in the slave trade, however, they did take part, and a lack of at least mentioning why McInnis did not include them in his study would have been helpful.

Similarly, all the white slave traders and enslavers are men; there is no mention of how white women might have played a role in the trade outside of fears of white slavery. This sexualizes white women and marginalizes them from a world they were very much a part of, as we know from They Were Her Property by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers. It could be that McInnis simply did not find images depicting female slave owners or participants in the slave trade, however, they did take part, and a lack of at least mentioning why McInnis did not include them in his study would have been helpful.

Again, I think the focus on one artist with one viewpoint perhaps weakens the book, though McInnis does use Slaves Waiting for Sale as a way to examine other visual representations of the slave trade. The only women in the book are the enslaved women, and McInnis makes them a crucial part of pre-, present, and post-sale action. He uses the expressions on faces, body language, and clothes in an attempt to analyze their role in the sale trade and even how they might feel about their unwilling participation.

By studying the visual abolitionist art that came out of the slave trade, McInnis introduces us to an important sensory experience of that trade. There is still work to be done by future authors, however, work that might widen the scope of whose eyes were are looking through. Despite shortcomings, this is worth the read.