How the Word is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. By Clint Smith. (New York: Little, Brown and Company. 297 pp. Cloth, $29.00, Paper $18.99.)

How the Word is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. By Clint Smith. (New York: Little, Brown and Company. 297 pp. Cloth, $29.00, Paper $18.99.)

Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity. By Donald Yacovone. (New York: Penguin Random House. 327 pp. Cloth $26.00, Paper $20.00.)

“The history we teach is the product of the culture we create, not necessarily of the actual history we made.” – Yacovone, p. 277.

Reception. Every historian wants it, but history more often than not does not cooperate. The way people reacted to the events in their histortical moment, political, social, economic, culture, has too often been deemed not important enough to chronicle in the record. This has certainly changed over the last century, but even for historians who seek out reception, it remains elusive, forcing the scholar to expand their search to new source bases, some perhaps pushed aside by other scholars as not being important enough or objective enough; but luckily that opinion seems to go against current trends.

Both How the Word is Passed and Teaching White Supremacy aim to investigate how slavery has been taught in American schools, but each takes a different approach. Smith’s sets his book in contemporary America, traveling north and south to investigate how slavery is taught today, or was taught as of 2021. Yacovone examines text books from throughout American history to prove that the North and South worked together to present a historical narrative devoid of the horrors of slavery and driven by the narrative of the Lost Cause in order to perpetuate national reconciliation following the Civil War.

Both How the Word is Passed and Teaching White Supremacy aim to investigate how slavery has been taught in American schools, but each takes a different approach. Smith’s sets his book in contemporary America, traveling north and south to investigate how slavery is taught today, or was taught as of 2021. Yacovone examines text books from throughout American history to prove that the North and South worked together to present a historical narrative devoid of the horrors of slavery and driven by the narrative of the Lost Cause in order to perpetuate national reconciliation following the Civil War.

Smith has an advantage over Yacovone. By setting his book in the present day and visiting sites related to slavery and how they present narratives of remembering and forgetting, he is able to get at the problem of reception. His experiences take the foreground: he is the one receiving the narratives of slavery. And less he be accused of bias, taking slavery-oriented tours of plantations, prisons, the New York City slave tour, and even a visit to a slave factory in Africa, he also attends a white supremacist rally. He interviews tour guides to better understand the resistance they come up against when they feature narratives of black experiences of the past, and he also interviews tour and event participants, including those at the aforementioned white supremacist rally. The people he polls are a small sample size, but the organic nature of his examination makes the experiences of tourists that more pressing when contrasted with the history of slavery they are enthusiastically or reluctantly imbibing.

What is the best way to teach slavery? Smith is an educator as well as an author of this historical work, and he says “I have come to realize that those conversations [about the history of slavery] with my students, now a decade ago, about how we might begin to understand our lives in relation to the would around us were some of the earliest sparks of this book. I tried to write that sort of book that I would have wanted to teach them. I hope I made them proud” (293). For Smith, reception is just as important as how slavery is taught. The two are inextricable.

One topic Smith does not discuss, which might seem a glaring omission but might also have been a deliberate choice, is how slavery was and is taught in American schools. Perhaps reception might have been to difficult to achieve there. It certainly would have made his book a lot longer. I can only speculate, but it might have something to do with the fact that he attempts always attempted to find sources outside himself, and those that are public facing, like plantation and prison tours, and history walks. Getting reception concerning school teaching and textbooks might have posed a problem he thought better left to other authors.

This is where Yacovone comes in. He attempts to determine how Americans taught slavery by examining a wide array of textbooks from across decades of American history. What he finds is disconcerting but not surprising: most textbooks in the North and South, attempting to inculcate white supremacy, either elided the history of slavery or attempted to place it in an positive light. It stands alongside David Blight’s Race and Reunion in emphasizing how textbook authors avoided taking a critical or at least truthful look at slavery in an attempt to reconcile the North and the South following the Civil War.

In fact, Yacovone says the problem of white supremacy found its most fertile ground in the North, not the South, and Northern textbooks played a larger role in disseminating the narrative of the Lost Cause and white supremacy than did textbooks in the South. Yacovone acknowledges that Northern texts most likely proliferated because the North had more publishing houses than the South, but it doesn’t excuse the lack of history of slavery and Blacks in those textbooks, and their support for white supremacy as a way to unite the nation through a shared education on that subject. He says, and it is worth quoting at length:

“Rather than Southern slavery, however, it was Northern white supremacy that powered the more enduring cultural binding force, planted along with slavery in the colonial era, intensely cultivated in the years before the Civil War, and fully blossoming after Reconstruction. Inculcated relentlessly throughout the culture and in school textbooks, it suffused Northern religion, high culture, literature, education, politics, music, law, and science. It powerfully resurfaced after the Civil War and Reconstruction to reassert control over the emancipated slaves to become the basis for national reconciliation, exploded in intensity with renewed immigration in the 1920s and ’30s, and endured with diminishing force to the present day. It succeeding as the superstructure of democratic society by allowing normal political conflict to proceed with the assurance that the assumed dangerous mudsill class (once controlled by enslavement) could pose no threat to the social order. Hence democratic equality rested on racial inequality and malleable definitions of whiteness. Moreover, it offered something more alluring than wealth, more effective than politics, and far more appealing than education. For even the poorest of its adherence, indeed especially for them, white supremacy imparts a sense of uncontested identity and, as the American philosopher and social critic Susan Neiman wrote, an otherwise unattainable level of ‘dignity, simply for belonging to a higher race.'” (6)

Yacovone’s argument isn’t necessarily new, but he is good at reiterating what other historians have said before him. He also expands his investigation outside of textbooks to narrate the changing trends in race-based thinking in the United States as history moved from the antebellum period, to Reconstruction, to the Civil Rights Movement. But he has one key ingredient missing: reception.

Without question, it is easy to believe that there simply are no sources that detail reception of the textbooks Yacovone investigated. It is easy to imagine that no one thought reception important enough to write down. Yacovone relies mainly on tracking how many editions publishers published each textbook to track popularity and usage. He also tracks their longevity to demonstrate the popularity of the ideas they taught. He attempts to link these trends to historical events, and demonstrates changes in the popular narrative by tracking them against trends in the subject matter and narratives in textbooks. Teaching White Supremacy is a solid piece of scholarship, but it feels like it is missing a piece. Could Yacovone have gotten closer to reception by boarding his source base, trying to find sources documenting how teachers made choices about what to teach, or perhaps finding book reviews or sources from educators about what they taught in their schools? These sources simply may not exist, but they are worth investigating to build on Yacovone’s work.

So each work has its strengths and weaknesses. Smith is able to probe reception of the subjects he chronicles, while Yacovone writes solid history of changing or static conceptions of slavery in American culture and specifically in American textbooks. They need each other to tell a complete story. Read in tandem, they reveal an American narrative of slavery fraught with disunion, but perhaps in investigating these topics, they bring us one step closer to a consensus that refuses to let Americans off the hook for the shameful way we have taught slavery and race throughout so much of our history.

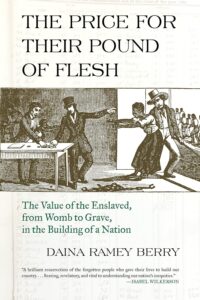

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of Enslaved, from Womb to Grace, in the Building of a Nation. By Daina Ramey Berry. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017. 212pp. Cloth, $27.95, Paper, $18.95.)

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of Enslaved, from Womb to Grace, in the Building of a Nation. By Daina Ramey Berry. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017. 212pp. Cloth, $27.95, Paper, $18.95.)